Worldviews Part Two:

Discussing Worldview Differences

The Apostle Paul told the Corinthians, “For though we walk in the flesh, we do not war after the flesh: (For the weapons of our warfare are not carnal, but mighty through God to the pulling down of strong holds;) We are destroying speculations and every lofty thing raised up against the knowledge of God, and we are taking every thought captive to the obedience of Christ” (2 Cor. 10:3-5). The message is that there will be forces at play, both within and without the church, that will need to be carefully weighed against scripture; and some will need to be fought, using not carnal weapons, but spiritual. Paul did not tell the Corinthians to destroy people, but to destroy speculations (‘logismos’ - computation, reasoning, imagination, thought). This instruction to use spiritual weapons has never been more needed. The need for combatting the logic of this world through scripture has perhaps also never been more needed. Eph. 6 describes the armor of God, which includes reliance on truth, prayer, faith, and peace. It is imperative that we express truth through the lens of love and kindness. This is no less true when interacting with others with whom we disagree on important issues. In the previous article, I discussed the progression of worldviews from the premodern era to the present, when many subscribe to postmodern beliefs that emphasize moral relativism rather than absolute truth. I also laid out how progressive Christianity is an outworking of this postmodern worldview, and has introduced some views into our society and into our community that are contrary to scripture. In this article, I will focus on principles of interacting with others in a Christlike way, even when we have different worldviews. I will also look at some of the reasons that well-meaning believers may see things differently from each other, when all are acting in good faith.

Interaction in a Polarized Society

Our society has largely abandoned the choice to disagree without being disagreeable. In North America, we live in a time of widely recognized polarization, especially on political issues (Pew Research Center, 2017). While our community largely eschews politics, we cannot ignore that most political issues overlap with religious and moral ones. Topics such as abortion, healthcare, immigration, and economics can often overlap with biblical principles related to how we treat one another. Even among believers, who share these guiding principles, there is widespread disagreement regarding their application. Such polarization may be exacerbated through the use of social media, although there is evidence both for and against this (Lau et al., 2017; Beam et al., 2018). Often, talking to someone with whom you disagree in ‘real life’ will be much less hostile than a similar discussion online. Adding to this difficulty of online communication is the bandwagon effect, in which observers weigh in, often heightening tensions and escalating bad behavior.

It can be discouraging and damaging when we witness believers engaged in discussions online that deteriorate into accusations, harmful labels, and unChristlike behavior. Often one will justify their behavior on the basis that another online party is saying something so unbiblical (or racist, blasphemous, or other word of choice) that one had to respond “firmly.” Those calling for more kindness in responses are said to be the ‘attitude police,’ as if they are straining at gnats (the attitude) while swallowing a camel (the objectionable argument being responded to). Sometimes the examples of Jesus turning over the tables of the moneychangers and his responses to the Pharisees are brought out to justify harsh responses. Justifying bad behavior citing such examples is not convincing, and I don’t think these examples are intended as object lessons for harsh online discourse and behavior. We have too many passages that give us direct instruction on what our interactions should be like, such as Phil. 4:5, which says, “Let your gentle spirit be known to all men” and 2 Tim. 2:24: “The Lord’s bond-servant must not be quarrelsome, but be kind to all, able to teach, patient when wronged.” Additionally, we know that we do not have the ability to read hearts and minds like Jesus did, which should give us a degree of humility in our interactions.

Principles of Interaction

The following suggestions are a combination of advice found in the Bible and guidance from other sources that can offer insight into interpersonal interaction.

Recognize That We Can Rarely Change Someone Else’s Mind

This is a hard thing to come to terms with, especially for those who consider themselves highly logical and analytical. To those individuals, it may seem that if you present a good enough argument, someone will be swayed. However, we all know from personal experience that is rarely the case. It is actually quite uncommon for someone to be convinced of a different perspective due to arguments with others. In fact, in some cases, when individuals are exposed to opposing viewpoints on social media, they can become even more convicted of their own position, leading to increased polarization (Bail et al., 2018). There is freedom in recognizing how powerless we are to change anyone else’s mind. Letting go of the need to control the beliefs and actions of others can take a lot of stress out of interactions with those who have a different opinion on important issues. We can seek to explain our own perspective and understand that of others, and often we have to leave it there. This should not be seen as a failure if we have conducted ourselves in a Christlike way.

Recognize That Differing Opinions Are Not Necessarily A Bad Thing

There have always been different ways of looking at things, even among believers. This has been true throughout Christadelphian history, and Christianity as a whole. Even Paul and Barnabas didn’t always agree (Acts 15:36-40). We should recognize that having differing opinions can be healthy (Prov. 27:17). Often the most functional religious communities will have members with a wide range of perspectives on important issues. This can cause discomfort at times, especially when trying to narrow down what we consider essential for fellowship. This has led to countless divisions, both within ecclesias and between them. But recognizing that there always has been, and always will be, disagreement on important issues should allow us to focus more on our attitudes and interactions, rather than on proving our view to be correct. Recognizing that differences are a reality, and that those differences are not always a bad thing, is not the same as accepting that all beliefs and actions are equally valid and acceptable. We should always stand up for the teachings of scripture; but we will only cause ourselves anxiety and grief if we do not recognize that we will never have complete alignment on some of these difficult issues.

Be Ready to Give an Answer

We know from scripture that we should be prepared to explain our beliefs to others, despite knowing that our efforts to persuade others will not always be successful. 1 Pet. 3:15-16 says, “...always [be] ready to make a defense to everyone who asks you to give an account for the hope that is in you, yet with gentleness and reverence; and keep a good conscience so that in the thing in which you are slandered, those who revile your good behavior in Christ will be put to shame.” This principle of being ready can extend to many topics, including our beliefs on issues impacted by our faith. Part of being ready means we need to have a solid understanding of our own beliefs on an issue. An equally important part of being ready has to do with our attitude. Are we prepared to discuss our worldview, based on our scriptural beliefs, with “gentleness and reverence”? If not, it may be wise to take a break from intentional interactions on controversial issues until we have gained control of our own emotions. This is, of course, not an excuse for avoiding giving a defense when asked; but some are more prone to seeking confrontation than others. There is nothing wrong with stepping back from such interactions if they cannot be handled in a Christlike way.

Seek to Understand A Position Accurately

It can sound cliché to say ‘seek to understand before being understood,’ but there is wisdom in it. We find the principle of listening before speaking in James 1:19, 20, which admonishes us that “everyone must be quick to hear, slow to speak and slow to anger; for the anger of man does not achieve the righteousness of God.” How often do we see others respond to an argument that we, as an observer, can see is not really the point the other person was making? Many may be familiar with the concept of the ‘straw man fallacy,’ in which someone attempts to tear down an argument that isn’t being made, often in an intentional attempt to discredit another; but it can happen accidentally as well. If you find yourself tempted to argue against a straw man intentionally, consider that this technique is not honest. The alternative is sometimes known as the ‘steelman,’ which means to argue against the strongest point for a particular position. That will often involve a lot of listening first, as well as asking questions, to make sure you understand the position. This article is not intended to be a review of logical fallacies, but being aware of those fallacies is beneficial for making sure your own positions are communicated in the strongest way possible, as well as for spotting weak arguments in others. Again, our goal is not to tear others down, but to believe and speak only what is true. If a position is true, we should not be tempted to make opposing arguments seem weaker than they are by misrepresenting them. When we see others doing this, it does not necessarily mean their position is automatically correct or incorrect; but it may indicate that continuing a conversation with that person may not be productive.

Seek to Understand Others’ Values

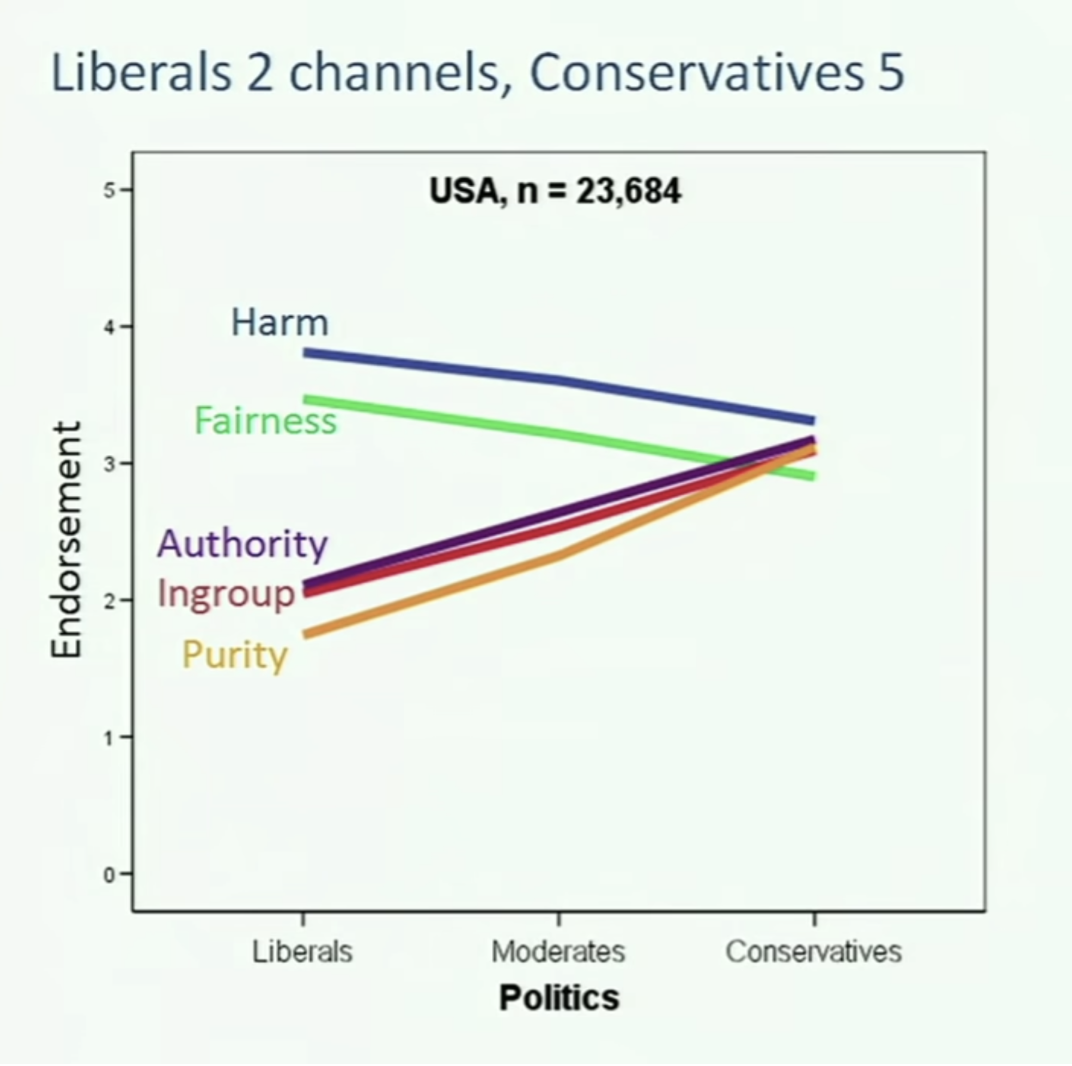

It’s beneficial to understand where others are coming from, especially when we disagree with their position. There is a theory called Moral Foundations Theory that has evolved over the past couple of decades, which offers one explanation for why we disagree (Graham et al., 2013). This theory posits that there are five foundational elements on which most people base their morality; and people will emphasize these elements differently. These foundations are Care, Fairness, Loyalty, Authority, and Purity. (Some of the research in this field has six foundations, and some will use slightly different names for the elements.) A questionnaire is available to take online at https://yourmorals.org/ (this site requires registration).

The values each of us emphasize will be significantly influenced by our worldview, which will have been impacted by many factors, including something as straightforward as our geography (e.g., people living in western countries tend to put more emphasis on protecting individuals from harm; whereas in traditional societies there is typically more concern with protecting traditions, groups, and principles of morality). And of course, within any society or locality - or religious community - there will be variation among those with different ideologies. As a general rule, those who are more liberal will emphasize the Care and Fairness foundations (which are sometimes called the individualized foundations) and value the Loyalty, Authority, and Purity foundations (sometimes referred to as the binding foundations) much less. Those who consider themselves more conservative appear to give all five foundations an approximately similar amount of concern.

Check Your Assumptions

Part of seeking to understand a position will involve clearing your mind of assumptions about the motives of others. How often do we hear the abortion debate deteriorate into a discussion of assumptions, such as “You hate babies” on one side or “You only care about babies until they’re born” on the other? No matter how strongly you feel about an issue, your position will only be made weaker if it involves accusations and assumptions. This does not necessarily mean that everyone who holds any position does so with pure motives. There is evil in the world. But almost every political or social position can be held by someone with good intentions. Often, what it takes to distinguish this motive from malice is an examination of the underlying value that is being emphasized.

It is important to acknowledge the assumptions we make about others. It’s equally important to understand and acknowledge our own biases. Our worldview and other factors will lead to instinctive reactions to situations and ideas we encounter. Being aware of our biases can bring a measure of objectivity to our discussions with others. Pretending, to ourselves or others, that we are more objective than we are will weaken our position and our character.

A graphic found in a Ted Talk by Jonathan Haigt, one of the researchers on this topic, is included for visual support here.

— Haigt, J. (2008)

When we interact with others who may place more emphasis on some of these elements, and less on others, than we do, this can lead to conflict. Instead of wondering how someone could be “so heartless as to think abortion is okay” or “so uncaring as to want closed borders,” consider asking what value the person you’re discussing an issue with may be emphasizing. This can lead to more productive discussions, and can often help identify common ground. For example, consider how much more productive and less hostile a conversation about abortion could be if it involved discussion of how to best care for the lives of the unborn and those experiencing an unwanted pregnancy, and how those two needs should be balanced, and considered alongside other values and considerations involved. For a thought exercise, consider a position you vehemently disagree with, and try to explain it in a way that makes no negative assumptions, ascribes positive motives to those holding it, and frames it in terms of those foundational values above. This exercise may not make you any more likely to change your mind on that issue, but may result in more compassion and understanding for those who hold the view you disagree with.

While there are critics of this Moral Foundations Theory, and no human-derived theory of morality will account for all nuances, I find it to be a helpful framework when considering the viewpoints of others with whom I disagree. And though much of the research on this topic has been in the realm of politics, it would be naive to assume believers take no position on political issues, even those of us who do not vote. Matters of public policy will impact us all. We may not identify with a political party. Furthermore, what’s considered conservative, moderate, and liberal in our ecclesias may not overlap entirely with those distinctions in society around us. That said, we could all probably place ourselves on that spectrum somewhere. As much as we may wish we could be separate from all discussions we consider political, these issues impact us and those around us, and are becoming prominent in our ecclesias as well. The answer is not to ignore them, but to address them using sound principles and a coherent biblical worldview.

Acknowledge That We Do Not Perceive Accurately

We know from scripture that our perspective is limited. God’s ways are higher than our ways (Is. 55:8-9). Only God and Jesus know what is going on in the hearts of others (1 Kings 8:39; Prov. 16:2; Matt. 12:25). We can easily misunderstand others’ words and intentions. There is evidence that we do not always accurately understand the perspectives and words of others as well as we think we do. This is true both in person and especially online. A recent study reported that people often perceive others to be more “outraged” online than they actually report being (Brady et al., 2022). We can probably all relate to the experience of reading a written comment and being unable to decipher the intended tone. And when we don’t have complete information, our minds will fill in the gaps, often incorrectly or incompletely. This may happen even in situations that are not highly fraught with emotion; how much more so when discussing topics that are inherently emotionally-charged, such as those most impacted by our faith and our worldview.

Misunderstanding another person’s tone or motive may not be the only way we lack accurate perception. We are also prone to making generalizations and stereotypes of others’ beliefs, even those with whom we share values. This has been shown in research, such as a study using the previously-mentioned Moral Foundations Theory, in which liberals, moderates, and conservatives were asked to answer questions according to their own beliefs and then according to the way they thought a “typical liberal” and a “typical conservative” would answer. The results showed that those of all ideologies exaggerated the differences when answering according to how they believed someone representative of an opposing viewpoint would respond, with liberals having the highest level of discrepancy in their estimations (Graham et al., 2012). Interestingly, both groups also exaggerated how they thought a “typical” representative of their own ideology (liberal or conservative) would respond. For example, not only did liberals estimate that conservatives would rank the Care foundation lower than they did on average; but conservatives also estimated that a “typical conservative” would rank the Care foundation lower than in actuality. This study also found that the differences in beliefs about “typical” liberals and conservatives were much more polarized than the actual differences in even the most extreme on each side. In other words, the perceived polarization was much wider than the actual polarization. No matter where we fall on the ideological spectrum, these studies provide a good reminder of the need for humility in our interactions, and in the need to challenge the assumptions we make about others’ motives.

Don’t Appeal to Emotion

God gave us emotions for a reason, but they are not good decision-makers. Our emotions may highlight the need to make a decision, but they should not be the driving force in that decision. We see this appeal to emotion in the media and in politics all the time. Politicians will often pick out an audience member who has been selected ahead of time, in order to highlight a personal tragedy that supports the need for whatever position they are espousing. The point is not that these stories don’t matter, but that they are being used to influence watchers to take a specific point of view on an issue that often has many nuances. Appeals to emotion will almost always be based on specific situations, and one could probably find many people on all sides of any issue who have experienced difficulties and tragedies as a result of whatever position is being argued for or against. A relevant cultural example is the argument for and against those who identify as transgender being allowed to use the school bathroom/locker room of the gender to which they ‘identify,’ regardless of their sex. On one hand, we are encouraged to think of the feelings of the males who identify as female and want to use the girls’ locker room. We are told that by not ‘affirming’ their gender, we will cause psychological damage to them. On the other hand, there are girls who have expressed they feel uncomfortable, even unsafe, with boys using the girls’ locker rooms. With emotional appeals, we are often left choosing whose emotions hold more value.

As with many issues in life, there is balance needed here. Arguing against using appeals to emotion is not the same as arguing for a lack of empathy or sympathy in our interactions. In fact, sometimes it is wise to share the emotional toll of a situation. Consider how Nathan the prophet approached King David, telling a parable, of sorts, in order to evoke David’s emotions, which in turn convicted his conscience and brought him to repentance (2 Sam. 12). However, in this instance, Nathan was using a story to bring David to an understanding of the truth of God’s ways that he was currently putting aside. This emotional plea had scriptural principles as its touchstone. There will always be nuances in decision-making but appeals to emotion often ask us to consider the emotional toll as the most important factor. I would argue that often, there is a clear scriptural answer; and considering the emotions of others should involve helping them see that truth, rather than letting the emotions dictate what is ‘true.’

Conclusion

Discussions about controversial issues can be stressful and emotional, full of tears and/or angry outbursts. When we disagree with other believers on important issues, this experience can be heightened by concern about the future of our community. Many see issues such as the abortion debate and the acceptance of homosexual and transgender lifestyles, to be issues rife with potential for future contention and division. We must face these times armed with solid scriptural principles - principles that apply to how we should treat each other as well as principles that apply clear Bible teaching on the moral issues of our time.

References

Bail, C. A., Argyle, L. P., Brown, T. W., Bumpus, J. P., Chen, H., Hunzaker, M. F., ... & Volfovsky, A. (2018). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(37), 9216-9221.

Brady, W. J., McLoughlin, K. L., Torres, M., Luo, K., Gendron, M., & Crockett, M. (2022, September 19). Overperception of moral outrage in online social networks inflates beliefs about intergroup hostility. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/k5dzr

Graham, J., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., Motyl, M., Iyer, R., Wojcik, S. P., & Ditto, P. H. (2013). Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 55-130). Academic Press.

Graham J, Nosek BA, Haidt J. (2012). The moral stereotypes of liberals and conservatives: exaggeration of differences across the political spectrum. PLoS One, 7(12):e50092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050092. Epub 2012 Dec 12. PMID: 23251357; PMCID: PMC3520939.

Haigt, T. (2008). The moral roots of liberals and conservatives [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/jonathan_haidt_the_moral_roots_of_liberals_and_conservatives

Lau, R.R., Andersen, D.J., Ditonto, T.M. et al. Effect of Media Environment Diversity and Advertising Tone on Information Search, Selective Exposure, and Affective Polarization. Polit Behav 39, 231–255 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9354-8

Michael A. Beam, Myiah J. Hutchens & Jay D. Hmielowski (2018) Facebook news and (de)polarization: reinforcing spirals in the 2016 US election, Information, Communication & Society, 21:7, 940-958, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1444783

Pew Research Center. (2017). The partisan divide on political values grows even wider. Retrieved March 9 2021, from https://www.people-press.org/2017/10/05/the-partisan-divide-on-political-values-grows-even-wider/.

Worldview Articles.

-

Learning Discernment

Moral implications of gender, sexuality, and identity.

-

Biblical Worldview Part One

The Creator’s Purpose.

-

Biblical Worldview Part Two

God’s Authority.

-

Worldviews Part One

Discussing Worldviews.

-

Exploring the Biblical Worldview

An introduction into the greater topic.

-

Related Content & Resources

A compilation of researched books, podcasts, videos, and other literature that may be helpful or edifying, regarding this topic.